To some, March might be just another ho-hum month, a rainy, cold passage that teases the start of spring. Here in the College of Letters & Science, March got us thinking about Mars.

That's right, the "Red Planet," named for the Roman god of war and the source of countless fables about invasions involving little green men.

Mars comes into prime viewing this spring (keep reading to find out exactly when). What better time to examine the glowing planet's influence on science and culture?

Looking at Mars allows a fascinating peek into the diversity of teaching and research here in L&S. From English professors teaching sci-fi to astrobiologists studying signatures of life on other planets, there is no shortage of thoughts and theories about the "Red Planet."

Here are some of the ways we have been, and continue to be, fascinated with our vivid neighbor in the sky:

March (the month) and Mars (the god)

Martius (Latin for March) launched the Roman year and took its name from Mars, the mighty Roman god of war and protector of agriculture.

War and agriculture might seem oddly paired, but burning an enemy's crops was a popular tactic in ancient warfare. Plus, Mediterranean weather dictated that most military campaigns wound down in October or November, before resuming in March, the same time planting season began.

Mars was "a convenient deity to pray to, in the sense that he can protect you in battle and therefore you're also protecting your land from enemy attacks," says Assistant Professor of Classics Grant Nelsestuen.

Unlike his Greek counterpart, Ares (a representation of "blind, rageful war," Nelsestuen says), Mars wasn't universally reviled in Roman culture. Yet Mars still wasn't an overly complex character.

"He's relatively more developed on the Roman side, but in many respects, he's still kind of a one-dimensional personality," Nelsestuen says. "I think the fact that he's the god of war just kind of trumps everything else and almost squelches any room for personality."

Like other major deities, the Roman god of war had a corresponding planet: the red one.

From god of war to land of fantasy

The telescope helped launch Mars' role in fantasy literature.

Nineteenth-century astronomers (incorrectly) believed they could see evidence of dried canals on Mars. Had intelligent life once existed there?

"Mars is often portrayed as a planet that was once incredibly like Earth, but is now a barren desert," says Ramzi Fawaz, an assistant professor of English. "For many authors, Mars has stood for a kind of Dark Ages."

Fawaz teaches a class on speculative fiction and fantasy which explores the roots of modern sci-fi. Stories featuring voyages to Mars and encounters with Martians began to appear in the late 1800s.

"Fantasy stories were a way to interpret the hyper-technological world developing all around us," he says.

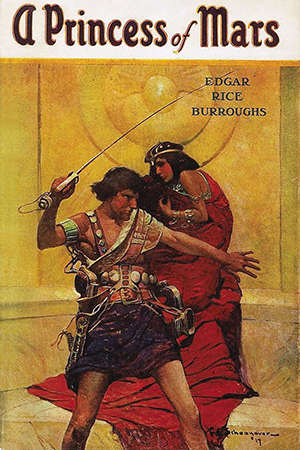

Fawaz's class, English 177, is currently reading A Princess of Mars, a classic work of science fantasy by Edgar Rice Burroughs, published in 1917.

A Virginian named John Carter — honorable, courageous — is miraculously transported to Mars, where he rescues a Red Martian princess and becomes enmeshed in the political fate of the "Red Planet."

"At first, the class thought A Princess of Mars was just fun," says Fawaz. "But by the end, they realize it's an allegory about race, gender, and masculinity at the turn of the century."

"The Martians have landed…"

Mars has also appeared in film, television, and, most memorably, radio.

Orson Welles' Mercury Theater radio adaptation of H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds— about a Martian invasion of New Jersey — sparked a panicked reaction among some listeners, who thought they were hearing live coverage of a disaster happening on home territory. Aired in 1938, the show most likely tapped into fear of the growing Nazi threat.

"Welles' genius was to place radio itself at the center of the story," says Professor of Communication Arts Michele Hilmes. "War of the Worlds showed the force of radio as a means of both information and propaganda, central to the war effort. It remains a powerful and convincing tour-de-force of radio drama, even today."

Science reveals

An image of a Martian valley that combines several frames taken by NASA's Mars rover Curiosity. This is the raw color version, as seen with Martian lighting conditions. (Photo courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

An image of a Martian valley that combines several frames taken by NASA's Mars rover Curiosity. This is the raw color version, as seen with Martian lighting conditions. (Photo courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

How naïve we seem, looking back! And yet, even with super-powerful telescopes and those plucky rovers, how much more do we really know about Mars?

NASA's Opportunity rover celebrated its 10-year anniversary on the planet in January. During its stay, Opportunity and its partner Spirit, which became inactive in 2010, have uncovered evidence of a watery past on the dusty planet. The more advanced Curiosity rover landed in 2012, transmitted the first video footage from the surface of Mars shortly thereafter, and last spring found evidence that, yes, the "Red Planet" could have supported life at some point.

Here on campus, members of the Department of Geoscience and the NASA-funded Wisconsin Astrobiology Research Consortium (WARC) are working to identify signatures of life that could indicate habitability on any planetary body, including Mars.

WARC researchers are studying Martian meteorites, but also examining rocks from Earth's early period, when no oxygen was present on the planet, to understand when and how atmospheric evolution unfolded.

"There is conclusive evidence that Mars was more habitable in the past than it is today," says Brian Beard, a senior scientist in the Department of Geoscience and a co-investigator in WARC. "[There is] strong evidence for liquid water, lakes, oceans. But the question is: How was Mars' atmosphere different to allow us to have liquid water? And why did it change?"

Look, up in the sky! It’s …Mars!

A look at how the night sky should appear April 8, when Mars is at opposition. Click for a larger image. (Graphic courtesy Stellarium & UW Space Place)

A look at how the night sky should appear April 8, when Mars is at opposition. Click for a larger image. (Graphic courtesy Stellarium & UW Space Place)

Look in the southeastern sky at night in the weeks surrounding April 8, when the planet will be at opposition to the sun (something that happens every 780 days). Mars will be smack-dab in the middle of the constellation Virgo — it will hang around Virgo into July — and the planet's red glow will be nearly as bright as the luminous star Sirius.

Stargazers with "a significant amateur telescope can get really good views," says Jim Lattis, the director of the Department of Astronomy's UW Space Place. Or, better yet, they can take advantage of public viewing sessions at Washburn Observatory or at Space Place. Lattis says the Washburn telescope was built for viewing planets on these occasions.

In years when Mars is very close to Earth — this year isn't one of them, unfortunately — telescope viewers can even see surface features, sights that have caused humans' imaginations to run wild.

"These days we have these [rovers] actually orbiting and sitting on the planet, so glimpses through the telescope aren't as exciting as they used to be," Lattis says. "But in the early 20th century … [Mars] was the only other planet where you could look up there and actually see what you could imagine as a habitable world."

The Department of Astronomy offers free public observing at Washburn Observatory regularly throughout the year. (Photo by Jeff Miller, University Communications)

The Department of Astronomy offers free public observing at Washburn Observatory regularly throughout the year. (Photo by Jeff Miller, University Communications)

So, what fascinates you about Mars?